The resistance songs or protest songs, considered after the April 1974 revolution as intervention songs, are made up of poems and songs denouncing a present of repression and arise as a struggle for a better world.

With no commercial purpose, often resorting to ballads and accompanied by the viola or guitar, they have a universalist message, free of any social constraint.

If we look at the great revolutions, there were always writers, musicians, painters and sculptors, in their genesis, provoking awareness to accept change. Fernando Namora, in Sentados na Relva states that “Art was our vehicle of protest; it was imperative that the novels and poems we wrote were the voice of those men whose scream was not heard, were the record of an iniquitous reality that urged report and rescue.”

At the base of the resistance songs, there were, many times, poems that expressed the feeling of an oppressed people, with the hope of freedom. In some countries, they are, above all, a protest song by pacifist and anti-war movements.

In the great challenges throughout the 20th century, artists were equally involved. Poets like Rimbaud, playwrights like Bertold Brecht or Sttau Monteiro, and country-inspired composers and performers like Woody Guthrie marked a generation that made art its fight.

Many still remember American folk-rock with the same concerns that characterized rock’n’roll and pop. Just remember Joan Baez or Bob Dylan with their guitars and the ballads of Zeca Afonso or Adriano Correia de Oliveira.

In Portugal, resistance songs assume a social and political function since the beginning of the 60s, namely with the outbreak of the Colonial War in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau. Many were the poets who found the exact word for that moment.

Even those who, apparently, did not denounce the regime, made songs where revolt is felt. Guitarist Carlos Paredes, for example, who considered music above all to be an act of love, often plays with friends, with singers like Adriano Correia de Oliveira (“Que Nunca Mais”, with texts by Manuel da Fonseca and arrangements by Fausto) and Carlos do Carmo (“Um Homem no País”, with lyrics by José Carlos Ary dos Santos), alongside poets such as Manuel Alegre (“É Quero Um País”) or encouraging and seeking to understand the sound experiences of younger musicians.

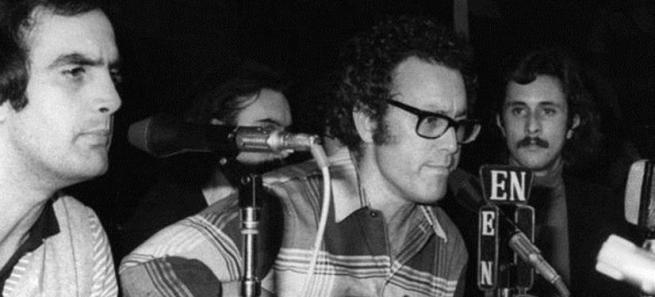

Due to the social conscience that art could form, many of these poets, composers and performers saw their records censored by the Estado Novo: Adriano Correia de Oliveira, José Afonso, Luís Cília, Manuel Freire, José Mário Branco, José Barata Moura, Sérgio Godinho, Carlos Alberto Moniz, Maria do Amparo, Teresa Paula Brito, Fausto, Carlos Paredes and many others.

Source: infopedia.pt

Image: setentaequatro.pt

Sérgio Godinho is also in the list? I can’t believe that!